It was 1985 and I was in South Sudan carrying out a feasibility study for WUS UK on the educational possibilities for the Ugandan refugee communities living there. These words, written by one of the refugees, spoke for all:

If to be a refugee was one’s wish and one’s desire, there would be no refugees in the world

I travelled around, hitching lifts with UNHCR vehicles, and visiting the different refugee settlements. I was staying in Juba, on the compound of the Sudan Council of Churches, in a set of rooms that resembled an aviary. My bedroom was out of sight at the back; in front there was a kind of large wire cage designed to be mosquito proof. It was here I sat writing up notes, chatting through the mesh to my neighbour in the next room, and meeting people who came to talk and share their hopes and fears.

Women had been under-represented in the WUS scholarship programme for Ugandan refugees and my brief was to explore educational opportunities for them. Many of the women were traders and for them literacy in written English and numeracy were important. News of my visit spread and a Sudanese woman teacher took me to a local initiative. The women met in the evenings in the local primary school sitting on small chairs, learning to write with pencil stubs on sheets of paper taken from the children’s exercise books. They said they were not refugees but they wanted to learn too, and just a small amount of money could make a difference.

A rather different task was to conduct interviews for WUS Canada who were offering scholarships for a resettlement scheme. Candidates had to write an essay to support their application and the quotation above was taken from one of these. I have never forgotten it.

Subsequently WUS established a resource centre in Yei and the first director was a Ghanaian with relevant skills and enthusiasm to work in a region that was unpopular at a time when war was starting again.

I then worked briefly on the Horn of Africa scholarship programme, covering Tina Wallace’s maternity leave, before completing a Master’s degree in adult education and community development at the University of Manchester.

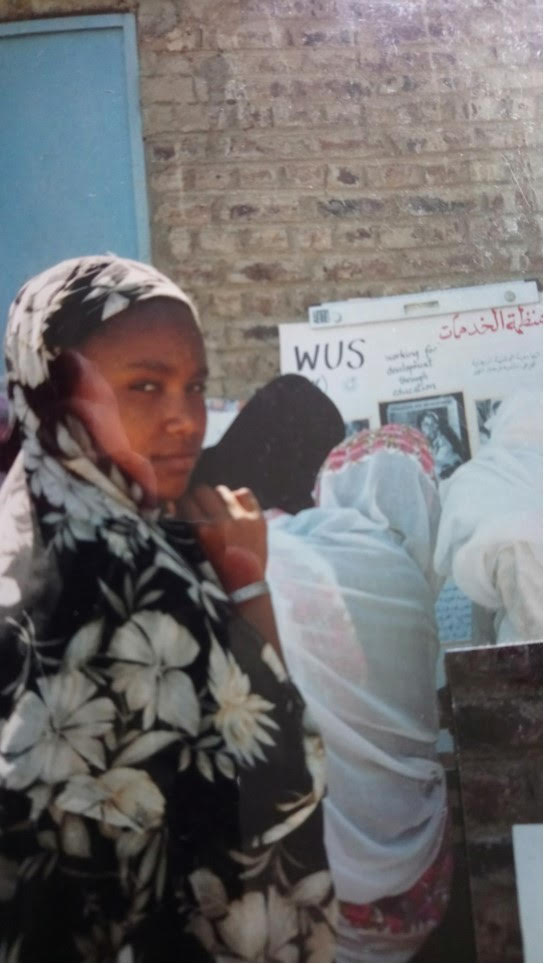

Four years later I was working for WUS again, recruited to co-ordinate an educational programme for refugee women in the settlements around Gedaref in Eastern Sudan. The women had come from Eritrea and were left behind as many of the men were resettled in other countries. It was a bleak and threadbare existence.

In the office of WUS Gedaref there was a photograph of Sally Rocket, the first Programme co-ordinator, who had been killed in a bomb attack at the Acropole Hotel in Khartoum. I never met Sally, but know she was remembered with sadness and affection. Between her loss and my arrival Birdie Knightley brought new encouragement and development to the programme.

A military coup had overthrown the democratically elected government just six weeks before I arrived; their hold on the country was to last for 30 years. There were rumours about the civil war with the south, the violence and crimes against humanity in the west, locally the secretary of a doctors’ union was said to have been ‘disappeared’ into one of the ‘ghost houses’, the unacknowledged torture centres. We were, perhaps, fortunate in not being near the capital. We were fortunate, too, that the name of WUS was known and respected because of the work undertaken in the past by members of WUS Sudan. They had been graduates who returned home, built primary schools and supported education in their villages.

In Gedaref we had regular visits from Sudan security officers, food was in short supply and the compound guard went out early every day to find lunch which all the staff ate together – an exercise in meeting everyone’s dietary needs and prohibitions. The programme continued and grew. There was adult literacy for both refugee women and Sudanese women, often of Eritrean descent. This was functional literacy and the modules on health were particularly popular. Skills training was offered in tailoring and, at the demand of the women, a project to raise chickens. This they ran independently with fierce rules and sanctions. Attendance at the literacy classes was variable -much depended on competing priorities, such as caring for a sick child, attending a funeral. This, as I learned later, is a common feature of such programmes. Nevertheless, the programme was valued. At the graduation ceremony before I left one woman spoke passionately about how, now that she was able to write herself, she would never again be humiliated by having to reveal personal matters to a professional letter writer. Another woman said people could take away everything, even her goats, but not the knowledge she now had.

I could not stay for a second year as the government would not extend my work permit. I kept in touch for a while, and the project manager, Hamid Abyad, stayed with me when he came on a training course. But eventually communication dried up, so it was a surprise and pleasure to learn recently from a former WUS trustee that the programme continued, and was providing an innovative model of adult education in the 90s.

For WUS the Sudan programme was an outlier. It did not fit readily into the format of the other educational programmes. Then, as now, Sudan seemed to many a faraway country of which we know little.

However, I think there was a positive impact on those whose lives the programme touched. I gained valuable understanding of refugee situations and particularly the experience of refugee women. I went on to work for a short time for the World Council of Churches’ Refugee Service in Geneva. After that I brought that experience to my work at Oxfam and then Responding to Conflict.

I can’t end this without a tribute to Sarah Hayward. We were colleagues and friends at Christian Aid for seven years before she went to work for WUS. It was through Sarah that I, too, worked for WUS. When she founded Skills for South Sudan, she invited me on to the advisory group. In retirement we worked together on refugee issues in the UK. She was a generous enabler of others and this is part of her legacy.

Bridget Walker

Bridget's original work with WUS UK in 1985 was to undertake a feasibility study for the possibilities for Ugandan refugee communities in southern Sudan. Her focus was on educational opportunities for women. She subsequently worked briefly on the Horn of Africa scholarship programme. In 1989 she went to Gedaref in northern Sudan to co-ordinate an educational programme for refugee women. Her post-WUS work included time with the World Council of Churches Refugee Service in Geneva, Oxfam GB and Responding to Conflict. She is a co-author, with Simon Fisher and Vesna Matovic of Working with Conflict 2 published by Zed in 2020.